On a pleasant summer afternoon in Mumbai last year, I made my way to the home of a prominent Hindi producer-director in an unusually quiet, green area of the city.

We had been discussing the film censorship scenario in the country for months before that; on this day, we spoke for several hours about the strategies this filmmaker was employing to get past the CBFC (the Central Board of Film Certification, popularly known as the Censor Board) and overly cautious streaming platforms.

“The legal teams of producers and streaming platforms would look at scripts earlier too for possible defamation cases and other routine concerns, but it’s different now—they’re going over every word with a magnifying glass because everyone is scared, and they don’t know what might hit them from which direction,” said the filmmaker, who I have interviewed repeatedly over the years.

This time, the interview was conducted on condition of anonymity for a story I was researching on censorship because this person had films and series at various stages of development, “and these days, you just never know...”

“You just never know.”

It’s a phrase I heard frequently over the 11 months I spent investigating film censorship in post-2014 India.

I heard it from those who gave me off-the-record interviews and from some who were willing to be identified for the story. Not knowing where objections, first information reports (FIRs), court cases, or violence might come from and for what reason is affecting filmmakers and filmmaking across India these days, more even than actual consequences.

This “fear of the invisible”—as I have quoted Anurag Kashyap as describing it—has led to what another brave filmmaker, Kannada cinema’s Natesh Hegde, called “a Censor Board in the back of our minds.”

This fear has not only prompted mainstream Hindi filmdom’s abject and collective capitulation before the government and the entire Hindutva establishment but is also very much on the minds of isolated dissenters in the Hindi industry, such as Kashyap and Anubhav Sinha.

Documentary filmmakers and off-mainstream independent directors, such as Hegde, who can be found in all languages, have shown great courage in this scenario—they, too, are conscious of how precarious their position is. An outsider may not guess this from how the mainstream Malayalam and Tamil industries have been determinedly pushing back against right-wing bullying and CBFC diktats, but even they are acutely aware of the risks they are taking by doing so.

Early in my investigation, a Tamil filmmaker who I was in touch with throughout said: “So far, the CBFC examining committees for Tamil and Malayalam cinema have been going along with the mood of filmmakers. They are not taking us head-on. Instead of opposing the resistance outright, they are merely keeping checks on the resistance.”

By year-end, this person said that statement was “obsolete” and that examining committees in Tamil Nadu and Kerala had become far more aggressive than they were earlier.

Meaning: the situation had deteriorated in a matter of a few months.

Less than three weeks since Article 14 published my investigation, history is repeating itself at the Bengaluru International Film Festival (BIFFes), which I had cited in the article. BIFFes 2022 rejected a bunch of independent (mostly Kannada) films that don’t conform to the image of India and/or Hinduism that the right-wing wishes to project—an image of love, harmony, and, it seems, ubiquitous vegetarianism.

On the list of films excluded that year was Abhilash Shetty’s Koli Taal, a slice-of-life saga about an old couple determined to cook a chicken curry for their grandson, who is on a visit to their home in rural Karnataka. Shetty, as I explained in the article, had earlier clashed with the CBFC examining committee when they insisted that he blur shots of chicken in a kitchen scene in Koli Taal, but despite these difficulties, he has since defiantly made Naale Rajaa Koli Majaa (English title: Sunday Special), the second film in what he says will be a chicken trilogy.

The Biffes 2025 programme was announced a few days after the article was published on 3 February 2025. On 13 February, Shetty posted an open letter on Facebook asking the organisers why Naale Rajaa Koli Majaa was not featured.

As he pointed out with an accompanying screenshot to support his claim, the screener he sent them had been viewed only once, although he had entered the film in multiple categories. “This raises the question, was it evaluated across all committees, or was the decision made without a fair review process?” he wrote.

While it may well be argued that a festival has the right to pick whichever films it pleases, Shetty’s questions regarding Naale Rajaa Koli Majaa merit attention, considering the evidence he has presented, BIFFes’ history with Koli Taal, and anti-establishment cinema in general.

Since Shetty spoke up, more voices have been raised. A group of producers has now taken BIFFes to court, demanding greater transparency in the selection process.

Resistance is not yet dead in Indian cinema, but the effort to repress it is getting stronger by the day, and it is bound to eventually impact the overall quality of the works produced in this era.

Among the over 50 people I spoke to during the course of my investigation, some told me they were struggling to even figure out a theme for their next film because there’s really nothing that could not potentially “hurt the sentiments” of someone somewhere either in government or the right wing at large.

As they kept saying, “You just never know…”

Read Anna M M Vetticad’s full story here.

Also read:

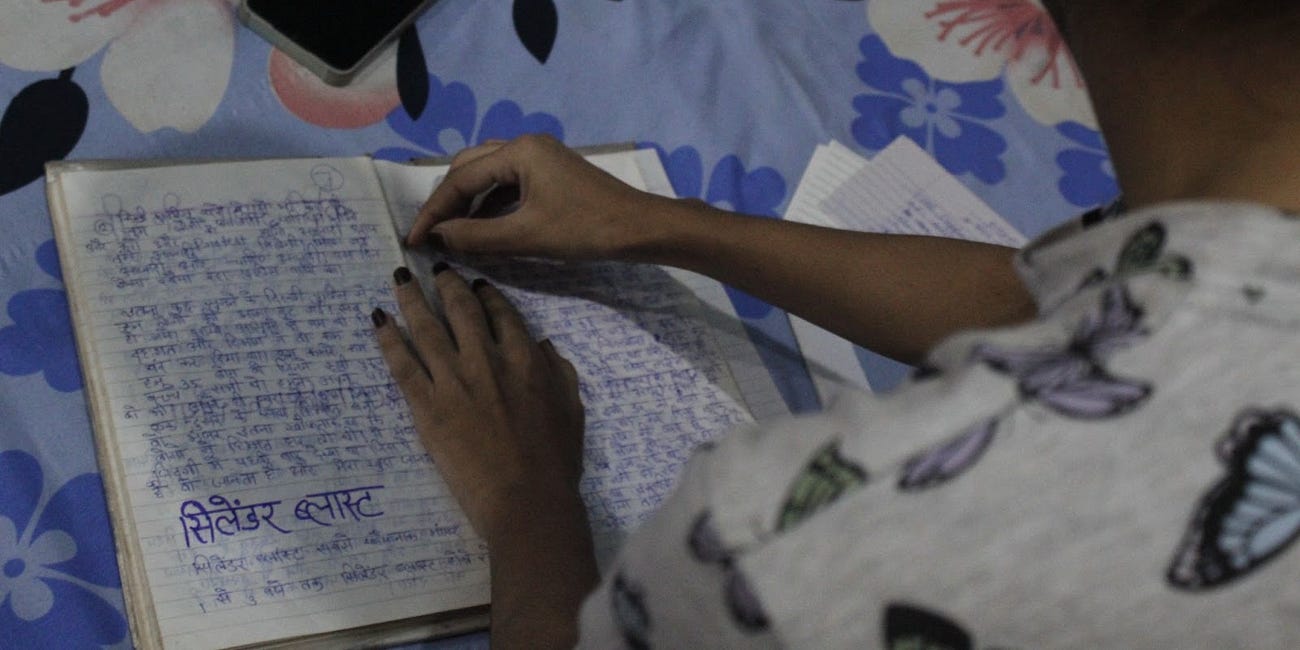

Field Notes: ‘This Diary Reminded Us Of The Book By Anne Frank’

After our group arrived at the Shiv Vihar metro station in northeast Delhi, a 28-year-old Muslim man, Abu Bakar, gave us directions over a call.