Between 2014 and 2024 alone, forest land measuring 173,396 hectares—four times the size of Mumbai—was “approved for non-forestry purposes”, a euphemism for clearing such land of trees and vegetation to make way for, among other things, roads, railway lines, mines, etc.

Over two days I spent with Jenu Kuruba Adivasis in southern Karnataka’s Nagarhole tiger reserve towards the end of April 2025, this question of extractivism emerged many times in conversation.

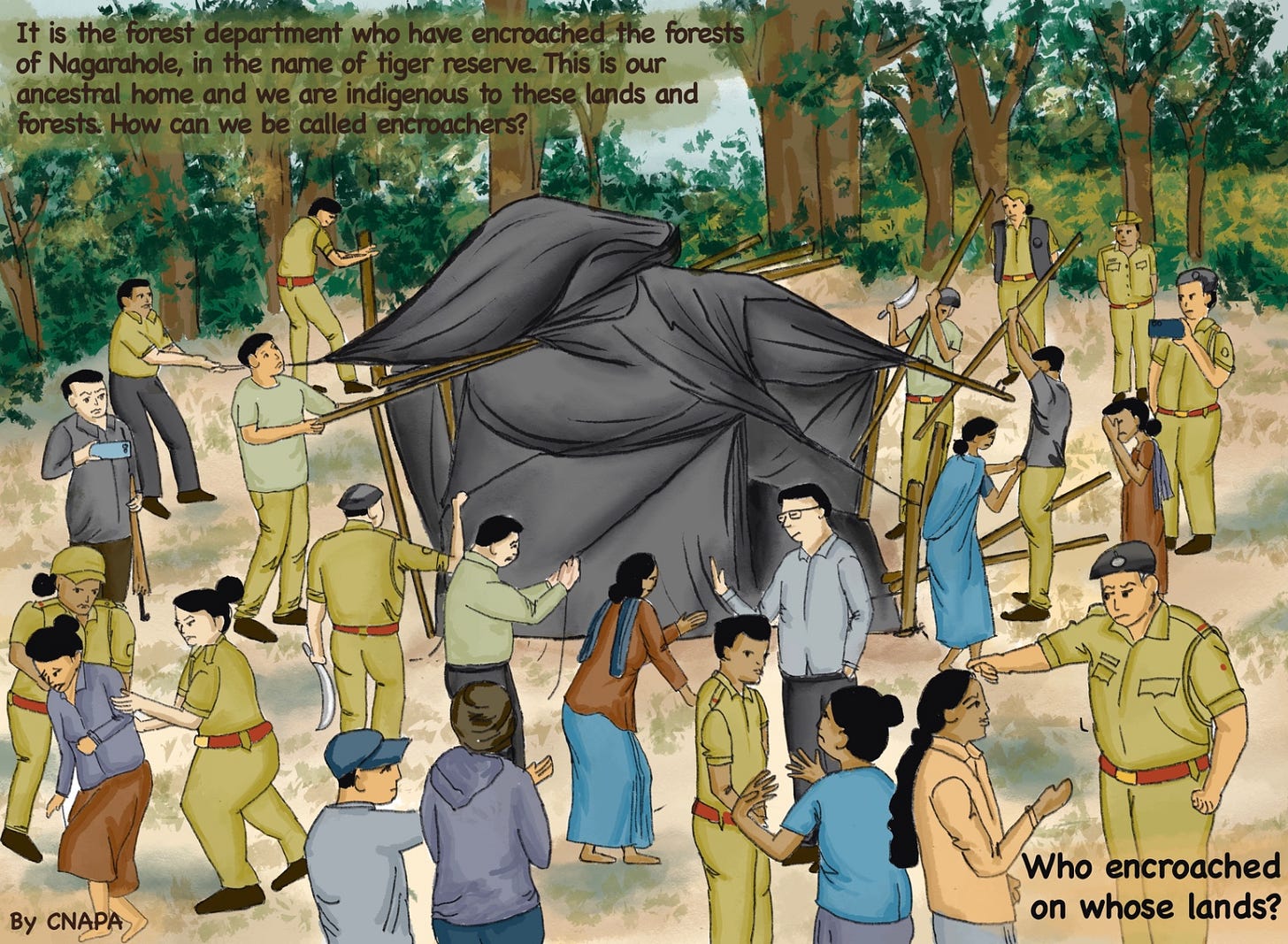

Fifty-two Jenu Kuruba families have occupied a tiny sliver of forest land in Nagarhole since 5 May, an act of defiance against their forcible eviction, without compensation, in 1986, and against subsequent denial of their rights over the land.

J C Thimma, about 60 years old, is among the senior leaders of the protest by residents of Karadikallu Attur Kolli Haadi, though he himself belongs to a neighbouring village. Over the decades, Thimma anna (big brother) has had several run-ins with forest department officers and the tiger protection force that patrols tiger reserves.

Between 1997 and 2002, Thimma anna was among the Jenu Kuruba leaders who challenged a Karnataka government-Taj group project to operate an eco-tourism resort or lodge in the forest. (The project was eventually cancelled.) Arrested during those protests, Thimma recounted, eyes twinkling, that forest department officers keen to oust the current protestors cite some of the very reasons that the Nagarhole Budakattu Hakku Sthapana Samiti (the Nagarhole Adivasi Rights Restoration Forum) did when it took the government to court in 1997.

“They say to Adivasis living in the national park that the forest is home to elephants, antelope, gaurs, and other animals, and that the forest’s biodiversity is precious,” he said. “That’s what we said in court. Was it not precious when they were seeking to build a resort here?”

In court, the Karnataka government had contended that the objective of an eco-tourism project was to “create awareness and appreciation about the need to protect the wildlife and the forests”. It claimed the project would not damage the bio-culture of the national park.

Almost three decades since that agitation, every one of the current Jenu Kuruba protestors remembered that the government considered a starred hotel’s jungle holidays for tourists to be in line with wildlife conservation plans, but not indigenous forest-dependent people and their livelihoods.

Thimma anna and other protestors said several tribal communities had been forced out of the forest upon its declaration as a national park, including Jenu Kurubas, Betta Kurubas, Yeravas and Paniyars, all people whose ancestors had been stewards of the forest, who had given the names for various regions of the forest that endure to this day.

In court, they had contended that much like some of the park’s endangered species, indigenous people’s numbers were dwindling too, and that they were facing near-extinction.

“One question that arises is whose forest it is,” said Thimma, “a question that we are all asking here as the long arc of our protests continues.”

Additionally, he said, tribals and forest-dwellers are forced to wrestle with the question of what kind of citizenship they enjoy when wildlife conservation frameworks reconfigure their relationship with the State.

“Our rights are constantly negotiated and contested, but mining companies or tourism companies do not seem to bear that burden.”

I had these conversations on the evening of a festive day when local Jenu Kurubas gathered from several villages at one of their spiritual sites in the forest. A wild elephant had visited them there the previous evening. A curious deer came by as we spoke, barely 20 feet from the clearing where I sat taking copious notes.

Thimma anna had been telling me that their history as a people remains a colonial history, their way of inhabiting the earth and their political movements both seen as inferior in some way.

Dusk was gathering when the deer arrived. Nobody moved to pick up a camera or mobile phone. Everybody turned to look, and the deer returned our gaze. Then, hooves barely disturbing the leaf litter beneath, it was gone.

Read Kavitha Iyer’s full story here.

Also read:

Field Notes: Hindu Father Searches For 2 Muslims Who Recovered Slain Son’s Body

“I’d like to ask them to come and visit our home so that we can thank them properly,” said Sanjeev Kumar Bhargav, speaking of the Muslim man a…